Understanding Student Loan Forgiveness

President Biden has proposed forgiving up to $20,000 of federal student loans for certain lenders, which will cost taxpayers roughly half a trillion dollars. He has also proposed making several income-based repayment options more affordable for borrowers—also costing hundreds of billions of dollars. What will that mean for student loans in the future and their effects on the federal budget?

What is President Biden proposing to do with federal student loans?

Full or partial federal student loan forgiveness was one of President Biden’s campaign promises. With 45 million borrowers and $1.6 trillion in federal student loans outstanding, there are many people who would like to have their student loans forgiven.

The details so far are as follows: The government will forgive up to $20,000 in federal student loan debt for anyone who received Pell Grants to offset the cost of their education, and up to $10,000 to non–Pell Grant recipients. Loan forgiveness is extended to borrowers earning up to $125,000 per individual or $250,000 per married couple.

In addition, President Biden has proposed a new income-driven repayment plan that lowers monthly payments for undergraduate loans to a cap of 5 percent of discretionary income; this plan also forgives any remaining balances after 10 years of repayment, as long as the original balance was under $12,000.

Another change is the expansion of the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program, available to some borrowers in public service. Currently, very few graduates qualify for PSFL. President Biden’s proposal vastly expands the number and types of nonprofit institutions where PSFL can apply. This expansion and new caps on income-based repayments could mean forgiveness of tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of student debt for large numbers of borrowers.

Lastly, President Biden has proposed doubling the Pell Grant given to recipients and ultimately making all community colleges free.

These proposals are all on top of the existing student loan repayment freeze that began at the start of the coronavirus pandemic and is set to expire at the end of 2022.

By offering more loan forgiveness to Pell Grant recipients, the Biden administration is making the argument that loan forgiveness is progressive in nature, meaning it benefits lower-income families more than higher-income families.

But research from Hoover visiting fellow Michael Petrilli highlights that student loan forgiveness primarily benefits well-off Americans. Borrowers with the largest balances are often those with advanced degrees and well-paying jobs. Around half of American high school students either do not go on to college or do not complete their degrees, meaning that taxpayer-funded benefits for student loans are being spent on those who are more educated and who presumably earn more money over their lifetimes.

Why is the federal government in charge of student loans?

Should the federal government be in the business of subsidizing and controlling student loans?

As Hoover senior fellow Richard Epstein argues, progressives in government “should reject policies that attempt to control private markets through inefficient regulations and subsidy schemes that favor their preferred constituents and are paid for by taxing the rich. Such an approach does not work for labor markets or medical services, and it cannot work for college education either.”

That doesn’t mean that subsidies for low-income students aren’t a good idea. Targeted student loan assistance is a better way to benefit the people who actually need the most help. Roughly 15 percent of student loan borrowers are delinquent or in default on their loans, which cannot be discharged in bankruptcy proceedings.

To hear more from Richard Epstein on President Biden’s student loan proposal, listen here:

Will student loan forgiveness make inflation worse?

Hoover visiting fellow Kevin Hassett reasons that student loan forgiveness will raise aggregate demand at the same time that supply-side policies become more restrictive, leading to higher inflation: “It’ll definitely make inflation worse. There are many people with student loans paying off their debt a little bit at a time, but if that is forgiven then they will have an extra $300 to $1,000 a month that they can spend. . . . That’ll increase the demand.”

Forgiving student loans frees up discretionary spending for student loan borrowers. While it isn’t predicted that forgiveness will raise inflation by a lot, it certainly isn’t consistent with the goals of the Inflation Reduction Act passed just two weeks prior.

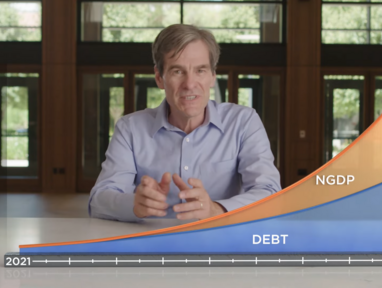

What are the fiscal effects of student loan forgiveness?

Michael Petrilli argues that student loan forgiveness limits other spending that could be used for better-targeted antipoverty efforts. As Petrilli points out, “a National Academies committee estimates that we could reduce child poverty by 50 percent with an additional investment of $90–110 billion a year in the Earned Income Tax Credit, housing vouchers, and SNAP benefits.”

In addition, many people are worried about what changes to the income-based repayment options will do to incentives for schools and their tuition rates. With the eligibility expansions made to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, it becomes possible for schools to raise tuition while total repayments remain constant for the subset of borrowers who expect to work in PSLF-related fields.

In this interview, Hoover fellow David Henderson notes that “tuitions are high because of government policy.” With the changes to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program and the caps on income-based repayments, the incentives for schools to raise their tuition will mean higher prices and more taxpayer-funded forgiveness.

It remains to be seen how many of these proposed changes will be implemented, how much they will cost, and how they will change the behavior of borrowers. But making student loans cost less for borrowers and more for taxpayers will likely lead to more borrowing in the future—and perhaps further rounds of loan forgiveness.