Environmental Policy Insight

What Causes Environmental Problems?

Before we can find the best solution, we need to understand the nature of our environmental troubles. From deforestation to polluted oceans and dirty air, environmental problems can be traced to what economists call “the tragedy of the commons.” The tragedy occurs when no one owns a particular resource, so no one has a strong enough incentive to take care of it.

Economists Terry Anderson and Laura Huggins highlight the dilemma by explaining why no one ever washes a rental car:

“Unlike the rental car company, which is quick to wash, wax, and polish, we don’t wash rental cars because we don’t own them and thus will reap no rewards from their future rental or sale value. The owner of the car, however, by maintaining the car, captures a return in the rental and resale market.”

When you own something, you have a significant financial stake in preserving and improving it. In contrast, when a resource is held in common, people don’t have as many reasons to care for it. Instead, they overuse or abuse it. You can see examples of the tragedy of the commons in all sorts of environmental issues. Deforestation, overfishing, and even air pollution all happen because no one owns the environmental good in question, so no one has incentives to ensure the resources aren’t squandered.

You can learn more about the tragedy of the commons in this video with Terry Anderson:

What Is The Right Amount Of Pollution?

That might sound like a strange question. The obvious answer is to say the right amount of pollution is zero. The reality, however, is that few would accept the trade-offs needed to live in a world with a perfect environment. Transportation, food production, health care, and all of the other parts of our economy that make us prosperous inevitably come with costs to the environment. If we tried to eliminate all of the environmental costs associated with our actions, we would find a world full of mass starvation, poor health, and poverty.

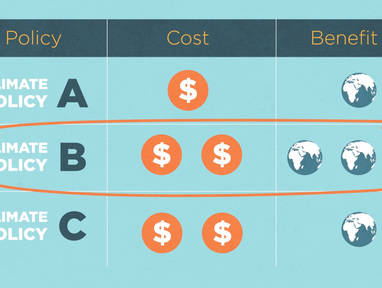

If zero pollution isn’t the goal, what should be? Our goal should be to make sure that the benefits society derives from an action exceed the costs to society from the action, and that includes the environmental costs. To learn more, watch this video on how to think about the costs and benefits of solving climate change:

The video focuses on the economics of climate change, but the lessons apply equally well to other environmental issues. By looking at the costs and the benefits, we can advance the economic well-being of humanity and preserve the environment.

What Is The Best Way To Solve The Tragedy Of The Commons?

You might think that the only way to solve environment problems is to rely on the government to issue regulations that strictly limit access and use of our environmental resources. But we can also solve many of our environmental problems by assigning property rights to individuals or communities. Property rights give individuals and communities an incentive to manage, protect, and improve what they own.

It might sound unrealistic to assign property rights to the air we breathe, the water we drink, or endangered animals, but governments have found creative ways to effectively assign property rights for important natural resources. Economist Gary Libecap explains how this works here:

“In both air pollution control and fishery regulation there has been an ingenious “property rights” solution. Because air and migratory ocean fisheries cannot be easily bounded into individual property rights, the alternative has been to designate private “use rights” to the resource, while not to the resource itself. What this means is that fishermen have a right to fish, but do not own the fishery. Similarly, firms have the right to pollute, but do not own the atmosphere. While traveling fish stocks and the air cannot easily be carved up into property rights, their use can.”

The video below highlights one example, where British Columbia overcame overfishing by creating a market for the right to fish. As the video explains, “By using market forces to make it in the fishermen's interest to have a healthy and sustainable population of fish, overfishing fell dramatically.”

This doesn’t mean that government has no role to play in protecting the environment. In the video below, Terry Anderson explains how government has a leading role in assigning and defending property rights.

Anderson coined the phrase “free-market environmentalism” to describe a flexible, market-driven approach to protecting the environment. This approach focuses on creating the right public policies so that the private incentives and interests of businesses, families, and individuals align with society’s best interest.

Why Can’t We Just Solve The Tragedy Of The Commons Through Government Regulations?

In contrast to the solutions described above, many environmentalists and politicians prefer to use government regulations to protect the environment. They want the government to write laws and enforce stringent rules to reduce pollution, punish poachers, and stop deforestations. Sometimes these rules work well. All too often, however, government regulations fail to improve the environment. In other cases, the regulations improve environmental outcomes but burden society with huge costs that far outweigh the environmental benefits. It’s really hard to get this balance right.

Politicians often choose poor methods for reaching their goals. They go beyond setting targets and goals for reducing pollution and instead mandate a particular method for reaching their goals. Economist Michael Boskin diagnoses the problem with many of these regulations: “These regulations usually used blunt instruments of command and control, specifying not only goals and targets, but also how these were to be achieved.” The end result is that politicians tend to pick very costly and inefficient methods for improving environmental outcomes.

For example, in an effort to reduce demand for oil, President George W. Bush enacted regulations that subsidized cellulosic ethanol production and mandated that energy companies blend cellulosic ethanol into their fuel. The regulations, however, failed to account for the scientific and economic feasibility of producing cellulosic ethanol. In the end, the regulations were largely removed. Boskin summarizes the reasons for the regulations’ failure: “The central failure here was its command that gasoline producers use a fixed quantity of an unproven new fuel, with no regard to price, cost, or feasibility, and no mechanism for adapting to experience.” In short, politicians unsuccessfully tried to pick the right technologies to achieve their preferred environmental outcomes.

Often rules that are purportedly intended to help the environment are instead used by politicians to advance their own interests or benefit special interest groups. Gary Libecap describes how California’s tax subsidies for zero-emission vehicles offer little environmental benefit but provide substantial benefit to a handful of wealthy Californians. The problem is that politicians do not always have the right incentives to adopt sensible regulations. As Libecap explains:

“Politicians and agency officials are not residual claimants to the social costs and benefits of their actions. They are motivated to respond to advocates. The result is excessive environmental regulation that benefits a few with costs borne by the broad citizenry.”

What About The Green New Deal?

The Green New Deal promises to overhaul the US economy to protect the environment and stop climate change. Among its many proposals, the deal would shift the country to 100% renewable energy, replace all gas-guzzling cars with zero-emission vehicles, and make every home and business energy efficient. While reducing the nation’s carbon footprint is an admirable goal, the Green New Deal makes the same errors that past environment regulations have made. Instead of offering feasible solutions that balance economic and environmental interests, it relies on heavy-handed, top-down regulations that underestimate economic costs.

For starters, the Green New Deal fails to account for the limits of today’s technology. It follows the same mistakes of the cellulosic ethanol rules discussed above by assuming that government can quickly subsidize and regulate feasible technologies into existence. For example, it assumes wind and solar power can deliver 100% of US energy demand. Richard Epstein explains the problem with this assumption:

“The fatal drawback of wind and solar is their lack of storability. Solar works when the sun shines. Wind works when breezes blow. Both often provide energy when it is not needed and fail to provide it when required. Any legal diktat that puts these renewable sources first will only produce a prolonged economic dislocation.”

Despite their technological limitations, wind and solar energy have strong and vocal supporters among environmentalists and many politicians. Their strong commitment to these solutions means they often dismiss alternatives sources of energy like hydroelectric and nuclear power, which promise reliable energy with little carbon footprint. For example, Boskin points out how California’s energy policy has actively undermined these more promising power sources:

“California’s legislature and regulators are so captured by the solar and wind lobbies that hydro is excluded from meeting renewables standards, and of the state’s two nuclear power plants, one is shuttered and the other likely soon will be.”

Solving our environmental issues, particularly climate change, is made even more challenging when environmentalists become wedded to their particular solutions at the expense of others. In this video, Jim Ellis explains why we should stop overlooking nuclear power as a viable alternative to carbon-heavy power sources.

Even beyond its unfeasible energy targets, the Green New Deal fails to account for today’s technological, political, and economic realities. For example, it proposes a massive investment in zero-emission high-speed rail without acknowledging or addressing the problems experienced by California’s failed high-speed rail initiative. California voters were promised a quick trip from the Bay Area to Los Angeles on a state-of-the-art train. Within a decade, however, cost estimates skyrocketed, and the promised speeds declined. You can read more about the failures of the high-speed rail plan in this article by economist Lee Ohanian.

What About Climate Change?

Climate change might seem like the kind of problem that can only be solved with burdensome government regulations and massive subsidies like those included in the Green New Deal. But there is a far more efficient method to deal with climate change: a carbon tax.

Watch this video to learn why a carbon tax would be the most efficient solution:

As the video explains, a carbon tax is an “efficient solution because those who create costs would pay for them, instead of shifting them onto others.” And unlike the Green New Deal and other top-down regulations, “the carbon tax would reduce carbon emissions at a lower cost than today's arbitrary and complex regulatory limits: Winners and losers wouldn’t depend on being politically connected.”

Higher carbon prices will give consumers more reason to find carbon-free alternatives. The businesses and individuals who derive the least amount of value from carbon will choose to conserve or find other options. Others who depend more heavily on fossil fuels for their livelihood would be permitted to continue operations but would now bear the full costs of their energy choices, including damage to the environment. This will maximize society’s welfare: the carbon-emitting industries that most benefit society would continue to operate, while those who don’t would find alternatives. Finally, over the long term, higher carbon prices will encourage inventors and entrepreneurs to develop new technologies to further reduce demand for carbon-emitting vehicles and energy sources.

Convincing the public that a carbon tax is the best policy is, of course, a challenge. Low- and middle-income families spend a larger share of their income on energy than high-income families and would therefore feel more of the tax burden. But this is true of any policy that increases the price of emitting carbon, whether it is a heavy-handed regulation or a carbon tax. It will have a disproportionate impact on lower-income families. Unlike the regulatory option, however, a carbon tax generates revenue that can be given back to low- and middle-income families. Proponents call this a revenue-neutral carbon tax.

Here is Boskin summarizing the merits of revenue-neutral carbon tax:

“A revenue-neutral carbon tax, levied per ton of carbon emitted with the proceeds rebated, is a far more effective and efficient method for dealing with climate risks. It would be neutral with respect to which technologies could most efficiently and effectively deal with the externality, while avoiding cumbersome, inflexible diktats from government bureaucrats trying to guess the future or succumbing to regulatory capture by the interests they subsidize and protect from competition and innovation.”

Conclusion

Top-down environmental regulations can sound appealing. They are designed with the best of intentions, but as Michael Boskin reminds us: “Good intentions are no substitute for the laws of physics, economics, and arithmetic.” As we have seen, the better approach is to find ways to align the incentives of private actors—businesses, families, and individuals—with the best interest of society. Doing so will ensure that future generations have economic opportunities and a well-preserved environment.

Sources and Further Reading

Economists George Shultz and Gary Becker explain why they support a revenue-neutral carbon tax in this 2013 op-ed. They answer questions regarding how the tax would be designed and how distributions from the tax revenue would work.

In this 2017 op-ed, Shultz and James A. Baker explain how a carbon tax gives private companies incentives to find the most efficient methods for reducing their carbon footprint.

In his 2004 book You Have to Admit It's Getting Better: From Economic Prosperity to Environmental Quality, economist Terry Anderson explains how economic progress and environmental improvements go together.

In a three part video series Just the Fracts, Terry Anderson and Carson Bruno explore the science, economics, and politics behind hydraulic fracturing.