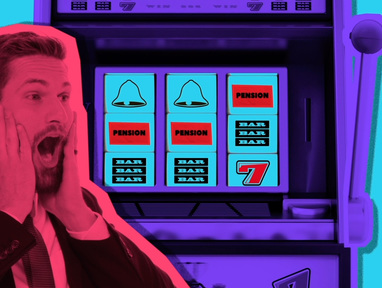

Public Pensions

How Big Is The Problem?

State and local governments have unfunded pension obligations that total over $4 trillion. They have promised public employees—teachers, policemen, firefighters, and other public servants—“defined benefit” pensions in their retirements. But they have not been setting aside nearly enough money to pay for those promises. Current taxpayers are already footing the bill for shortfalls in funding, and the gap is growing every year.

When pensions are underfunded, taxpayers essentially pay twice: once to cover current public employees who provide them with the services they are receiving today, and again for the retirement pensions of the public employees that worked for the city or state in the past. This is increasingly happening now, as pension contributions are among the fastest-rising budget items in states and cities.

Even as states and cities pay larger portions of their tax revenue to cover pensions, their total liabilities continue to grow. In California, for example, state and local governments would have needed to contribute 26 percent of their tax revenue toward pension liabilities to prevent them from growing in 2017. But instead, they only contributed 12 percent.

The market value of unfunded pension liabilities reached $4.145 trillion in 2017. For more numbers, read the 2019 update to “Hidden Debt, Hidden Deficits” here.

To learn more about the problem, watch “The Risky Business of Public Pensions” here:

How Widespread Is The Pension Crisis?

State and local governments all over the country are in trouble when it comes to unfunded pension obligations. No state has a funded ratio of 100% when using market valuations. Most are below 50% funded. Many cities are in even more trouble.

Click here to use our interactive map of pension liabilities by states and major cities:

It’s important to remember that pension funds are often dedicated to particular public positions. For example, in a given state, firefighters may have their own pension fund, police officers may have another, the teachers their own, and so on. As a result, fixing unfunded pension obligations means working with many funds and convincing each and every one of them to change their accounting practices.

Watch the first episode of Pension Pursuit to learn more:

Many Managers Of State And Local Pension Funds Say They’re In Better Shape Than You’re Reporting. Why Is That?

The problem is worse than what is reported by pension-fund managers. That’s because state and local governments are assuming much higher investment returns than is appropriate. Since pension promises are treated as guarantees under the law, they should be backed up with guaranteed, risk-free assets like Treasury bonds. But they’re not. Instead, they’re backed by stocks and bonds whose value fluctuates based on market conditions.

Watch as Hoover Senior Fellow Josh Rauh explains why taxpayers will eventually have to bail out public pensions:

Currently pension-fund managers estimate future returns on their investments using fairly aggressive assumptions. Typically, this figure has been about 7.5 percent. This means that they are effectively assuming the amount of money the city or state sets aside will double every 9 years. But the probability of obtaining nearly 7.5 percent returns over a 30-year period is only about 25 percent. In other words, pension officials are budgeting based on overly optimistic hopes for investments returns. As long as they assume that their investment returns will pan out, they can declare their pension obligations more funded than they really are.

As an example, consider an individual who borrows $100,000 due in ten years at 0% interest. The individual spends half of the funds today on discretionary spending, such as a trip around the world. The remaining $50,000 is placed in a portfolio of stocks and bonds, which historically has had returns of around 7.5%. The individual then applies for a mortgage and is asked to disclose all his assets and liabilities. The individual declares that his net debts are zero, on the grounds that the $50,000 is presumed to double in ten years to pay off the $100,000 debt. Of course, an individual who neglected to disclose this arrangement would have committed financial fraud. However, a government entity with $50,000 in assets to pay a $100,000 pension payment in ten years is allowed to declare this promise “fully funded.”

To learn more, watch “Kicking the Can: Concealing Budget Shortfalls by Underfunding Pensions” here:

Instead, pension funds should estimate future returns using the risk-free rate on government bonds. That number is a little less than 3 percent. Since those pension promises have to be paid, their funding should come from money that will absolutely be there in the future without having to rely on taxpayers to fill in any shortfall.

Why Should Pension Funds Assume A Low, Risk-Free Rate When The Returns On Stocks And Bonds Is Traditionally Much Higher?

It must be understood that most observers of financial markets today believe a 7.5 percent compound annualized return is wildly optimistic and unlikely to be achieved. This has been pointed out by investing luminaries such as Michael Bloomberg and Warren Buffett. While you may assume that stocks in the long run are less risky and are likely to march ever upward, the experiences of other countries suggest that you cannot assume that time will bail out pension systems from the possibility of poor stock returns.

For example, the Japanese stock market as represented by the Nikkei 225 rose to a high of 38,916 points at the end of 1989. As of April 2016, the index stands around 18,500, representing a capital loss of 52.5 percent.

With this in mind, we must remember the importance of being careful and sensible when making assumptions about investment returns, as countless public employees are depending on the promises made by politicians and union leaders regarding their pensions and benefits. These employees are planning their careers and retirements based upon these figures, so it only makes sense to use a responsible, dependable, and most probable rate of return.

And since future pension payments are treated as legal guarantees, any funding shortfall requires tax increases on future taxpayers. In a way, risky pension accounting ends up as a tax increase that voters never approve at the ballot box.

To learn more about historical returns on investment, watch “Unfounded Optimism: High Investment Returns Are History” here:

What Happens If Pension Funds Run Out Of Money?

When a pension fund falls short, taxpayers are on the hook to make up the difference. General tax revenue must be diverted from other spending priorities, like education, public transportation, or public safety.

If pension funds fall really short and tax revenue isn’t sufficient to plug the gap, the possibility of bankruptcy arises.

There are three ways a state, county, or city could address the financial distress of bankruptcy: taxes could be raised on the area’s citizens, cuts could be made to the salaries and benefits of the public employees in the pension system, or municipal bond holders could absorb the losses. However, in many states, pension promises to public employees are ostensibly protected in the states’ constitutions.

Take, for example, the bankruptcy that occurred in 2013 in Detroit, Michigan. Article 9, § 24 of Michigan’s state constitution reads as follows: “The accrued financial benefits of each pension plan and retirement system of the state and its political subdivisions shall be a contractual obligation thereof which shall not be diminished or impaired thereby.” Despite this protection, the pension system’s benefits were cut by 4.5% as part of the bankruptcy, which also cost pension recipients inflation adjustments. Municipal bond holders fared considerably worse. They only received between 14 and 75 cents on the dollar, depending on the type of bond they held. Many of these bondholders were under the illusion that municipal bonds were essentially risk free and provided an easy way to shelter their retirement savings from taxes while earning fairly high returns.

What must be stressed though is the sad reality that still persists in Detroit today: despite the significant measures that were taken to address the situation at the time of the city’s bankruptcy, its pension fund is still subject to the same structure and accounting principles, and therefore the underlying issues have not improved. These pension funds are still underfunded and are potentially one failed, risky investment away from collapse. And the same is true of many other cities and states in the United States.

This example also highlights the apparent seniority of pension benefits over municipal bonds in terms of payment in the case of municipal bankruptcy. If pension benefits are virtually guaranteed, their cost to the public (and values to workers) should be measured using the very low yields on very high-grade bonds.

Josh Rauh explains further in “A Few Trillion Short” here.

How Does The Funding Shortfall Affect People Right Now?

Public pension shortfalls may seem like a problem for the future. But the truth is, pension fund shortfalls are eating away at state, city, and county budgets across the country every year. The increasing cost of covering gaps for retirees means that existing policy priorities cannot be funded as intended.

It can also be difficult to disentangle where spending goes. Larger spending on public safety, for example, may look like a boost to active-duty police officers. But often it means more is being spent on retirees and less on active employees. If pensions were funded in an appropriate manner, that wouldn’t be happening.

To learn more, watch "Off by Trillions: The Reality of Our Pension Problem” here:

What Will It Take To Fix Public Pensions In The United States?

Pension fund officials need to do two things in particular to restore their funds to solvency. The first is to make more realistic assumptions about the investment returns their funds will achieve. The second would follow almost automatically from the first: contribute more to their pension funds. This is because pension contributions are calculated based on actuarial shortfalls. If funds use more realistic (lower) investment target rates, then annual contributions necessarily must rise.

Making these two things happen in practice is another story altogether. Perverse incentives for both union leaders and politicians are the reason why. Union leaders are focused on obtaining the highest possible total compensation for the public employees they represent during the collective bargaining process (for the majority of states that allow collective bargaining). If these terms are agreed upon with the states’ politicians, then it is incumbent upon the politicians to make the math work and assure that the promises can be fulfilled. From the politicians’ perspectives, it is advantageous to be supportive of public employees, because their unions often wield disproportionate power in the political processes of these states. Capitulating on increasing promises to public employees is often the path of least resistance in politicians’ reelection campaigns.

These situations are precisely why high-discount rates have become so attractive to politicians: they make it appear as if the pension funds are more funded than they actually are. More money in the states’ budgets can therefore be allocated to other projects and services that are intended for the wider public. However, as has been mentioned earlier, this structure is unsustainable over time and places future taxpayers and public employees at risk.

Absent a financial crisis or bankruptcy proceedings, pension fund shortfalls will only be fixed through a gradual reduction of assumed investment returns, a corresponding increase in active contributions, and a restructuring of future benefits that prevent unfunded promised benefits from growing even more.

To learn more, listen as Josh Rauh talks to Russ Roberts on EconTalk: